By John Gunnell

Russ Truelove crossed his final finish line on April 25, 2018 at age 93. This “Connecticut Yankee” was a true slice of American stock car racing history. Truelove was born in 1935 and started getting interested in racing cars when he was 10 years-old.

Russ wasn’t old enough to drive then, but he didn’t wait long. He got his driver’s license when he was 16. The date of Jan. 14, 1941 is burned into his mind. He is very proud to tell people that he’s never had any serious accidents when not on a racetrack.

Russ left high school in 1942. Like many members of his generation, he went into the Armed Forces. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy and served aboard the USS Sherwood in the Pacific. After being honourably discharged in 1946, Truelove started racing at East Coast tracks. He drove a 1947 Crager and raced at places such as Danbury, Conn. and Rhinebeck, N.Y. He started driving on the NASCAR circuit seven years later.

Russ worked as service manager for a Ford dealer in Waterbury, Conn. and later held a similar job with a Lincoln-Mercury dealer there. He met Bob Sahl, the Northeast Representative of NASCAR. Sahl handled all the NASCAR tracks in New England. Most of the action was modified stock car races on smaller tracks up north. In 1955, Russ purchased a 1955 Ford and took it to race on the old beach racing course at Daytona. Back then the four-mile beach course consisted of sand and a paved portion of highway.

Truelove competed with legendary drivers such as Tim Flock, Frank “Rebel” Mundy, “Fireball” Roberts and Lee Petty (Richard’s dad). The cars driven by independent drivers like Russ were usually purchased at a local dealership and driven to the track, which is just what he did with his Ford. They were basically regular production cars with taped headlights, a roll bar inside and the doors chained shut with the chain I-bolted.

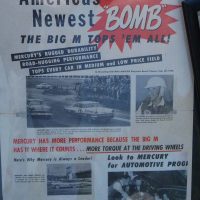

One day late in 1955, Truelove went hunting with Sahl. The NASCAR rep told him that since he had gone to Daytona with a Ford in 1955, he should go with a Mercury in 1956. The Mercury Monterey was heavier than a Ford, but it had a 312-cid V8 compared to a 292-cid used in Fords. Unlike some NASCAR Mercurys that were beefed up by tuners of the day, such as Bill Stroppe, Truelove’s car was a showroom-stock vehicle. In fact, it was actually a salesman’s demonstrator. Truelove bought the car on the installment plan. “You paid $50 a month for six months and then you got a big surprise,” he recalls.

Years later, if you asked Russ if the Merc was original, he was likely to say something like “The hell it is!” However, he kept the car until at least 2009. The frame was original, but not the body. In 1956, while racing the Merc on the sand at Daytona Beach, Truelove got his picture in Life magazine, but for the wrong reason. He had downshifted while entering the North Turn at 130 mph and his right tire dug in. He went into a skid and rolled the car over six times. It was a hell of a way to earn some media attention!

Russ survived the accident, but he did spend the night in a Florida hospital to “kind of clear” his head. After he was released, Russ started rebuilding the Mercury. He got a new hardtop body from the factory and put the car back together again. He raced for another season, but when the V8 blew up during the 1957 campaign, he packed it in. He could not keep up with the out-of-his-pocket costs of running as an independent in those days. Fixing the car up with his own money got too expensive and he quit racing.

Russ made “piecemeal” repairs to the car after getting the Monterey back together, since he actually used the Mercury as his pleasure car for a time. After that, he went to work for Bill Leer in Grand Rapids, Mich. and the car was stored at his dad’s house. The Mercury remained at his father’s house for many years and was very well preserved.

Truelove’s two top-10 finishes in NASCAR Grand National racing were enough to satisfy Russ, at least until 1989, when his wife gave him a Spec Racer kit car for a Christmas gift. He ran that car, a four-banger, in Sports Car Club of America races at age 62. He continued until the time he was bumped from behind in one race and slammed the car into a wall. Track medics convinced him that he was getting too old for auto racing.

Truelove was into racing for the sport and not to make money because he had a job and he knew he was better off working for an income. His job took priority, but he was always an enthusiast. He always believed that NASCAR played a very important role in keeping racing alive in the United States during a very difficult period for motorsports.

“That was NASCAR back when old Bill France ran it,” Russ told us. “In 1955, there were five AAA racing drivers killed. Then, along came the Spill – a bad wreck in Europe that killed 82 people. Triple A announced it was dropping all its support of auto racing in July of 1955 and then an Oregon Senator introduced a bill to ban auto racing by the end of 1955. He tried to get Eisenhower’s attention on it, since so many people were killed.”

“They brought out things like dual carburetion, which started with Hudson, and they were winning races,” Russ explained. “France saved racing by getting the factories involved. ‘Showroom stock!’ he said, but he pointed out, by the same token, that racing was adding to the safety of showroom cars. And, by the end of 1955, there was no more talk about cancelling auto racing. They—NASCAR—had a whole schedule on for 1956.”

Russ spent his later years in Waterbury, Conn. and had served as a director of The Living Legends of Auto Racing, Inc. (www.livinglegendsofautoracing.com). This group was founded in 1993 to recognize, honour and promote the pioneers of beach racing and stock car racing. The organization had over 600 members from around the world and was set up as a 501-C-3 non-profit group. The all-volunteer Daytona-based organization hosted a variety of activities throughout the year and published a quarterly newsletter called The Cannonball. The free Living Legends of Auto Racing Museum of Racing History is operated in South Daytona, Fla. For museum information call (386) 763-4483.