2019 Chevy Silverado in the Arctic

It’s just a gravel road. It’s rough, but no rougher than many roads scattered across the country. So why drive it and write about it?

For Chevrolet Canada, I suppose it’s about living up to its tag-line “find new roads,” and this gravel road is one of the newest in the country. But the main reason we recently drove the new 2019 Chevy Silverado north from the town of Inuvik NWT, was because of what this gravel road now connects to.

This 138-km gravel “highway” has become the last link in a chain of roads that now connects (for the first time) all the rest of Canada to our third national coast on the Arctic Ocean. This “connection” has been a dream 150 years in the making. Since Confederation in 1867, each successive government has made it a priority to connect all of Canada’s regions by road and rail. Early on, uniting the Pacific and the Atlantic coasts was the priority, as this is where most of our people lived – that early push of a fledgling country was also a necessary effort to cement Canada’s claim of being a nation from coast-to-coast. The Trans-Continental railroad was completed in 1885, bringing British Columbia into our union. This monumental effort was followed by a never-ending program of road building in the decades that followed as Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta joined Confederation.

This finally resulted in a joining of provincial highways into the continuous “Highway One” or Trans-Canada Highway. This was a federal effort that began in 1950 (soon after Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949). However, the last sections of this 7,812-km road were completed in just 1971. This country is huge and it has taken us a while to join Canadians together – east to west.

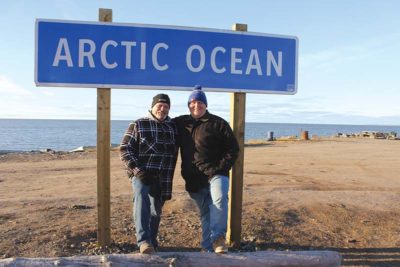

Today, a road-trip to the village of Tuktoyaktuk, North West Territories, situated on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, is possible from any starting point in Canada. Leaving from St. John’s, Toronto, Vancouver? No problem, get in your car and head north till you arrive in Tuk. This long-inhabited village situated in the delta of the Mackenzie River, far north of the Arctic Circle, is now on the only road that touches this most remote shore of our country.

For me, though, time was short, so I flew from Edmonton to Yellowknife, then after a brief stop-over, another hour north to Inuvik. This town of some 3,000 people is already 200 kilometres north of the Arctic Circle and, until last year, was the end of the road. That road, the Dempster Highway, which runs northeast from Dawson City, Yukon, is its only connection to the rest of Canada and until recently the furthest north you could go by car.

Frankly, travellers who make it to the end of the highway are still such oddities that it prompts locals to flag you down just to ask you where you are from. On the other hand, I realized as I drove through the hamlet that I was seeing a settlement in a pristine state, looking as it has for as long as it has existed.

As the inhabitants of Tuk have yet to take advantage of the coming tourists, there are no hotels, restaurants or gaudy tourist traps. This is a unique time capsule of Arctic life – though I fear it won’t last, as folks head up the highway just so they can say they did.

The Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk highway is known locally as Highway 10. As I said earlier, it’s a gravel road. That in itself is nothing special and as for the new Silverado, driving it was just fine. I have already reported on the new Silverado, so for this excursion it was the backdrop of the highway that made the trip special. So, I want to stress, it’s not implied that because a road is north of the Arctic Circle, it’s somehow more difficult to navigate than any gravel road anywhere else in the country. Still, what a place to do a truck review.

So, while it’s only 138 kilometres long, Highway 10 passes from boreal forest to the Tundra – losing all evidence of trees around half-way to Tuk. It is also the most winding road I think I have ever been on – as it runs through and around the water courses and lakes of the massive Mackenzie River delta. The turns are constant and there are just as many elevation changes as turns. For this reason (and the looseness of the gravel), the speed is restricted to 70 km/h.

The road itself is a marvel; because of the water (you are never out of sight of some kind of water as you drive), there are 359 culverts under the highway and eight bridges over water courses. But the most striking feature of construction is evident in the first few kilometres of travel – in places, you are over 30 metres above the surrounding land. The highway is built on massive berms of aggregate and gravels varying in height from place to place, all dependent on the need to preserve the perma-frost that lies below the construction. This one fact, preserving the perma-frost, created unique building challenges that then required very special solutions.

This was a hard-learned lesson probably first encountered on a grand scale during the construction of the Al-Can highway during World War II. That project (working its way north to Alaska) employed southern road building techniques, only to discover that after the surface of the tundra was broken, overnight trucks and bulldozers sank into the thawed, bottomless bog. It was only then that they realized that any progress at all was due to the frozen ground they were on.

Experiences like these were what forewarned the construction crews who tackled the Inuvik to Tuk highway. They started with the preservation of the perma-frost as their first priority. Under Highway 10 is a cloth membrane that insulates the ice, and above it is hundreds of tons of aggregate that do the same thing. Each section of the road was evaluated for heat sensitivity and then the appropriate amount of gravel piled on it – the intent being to never allow any heat from the road surface to penetrate to the ice.

Furthermore, there are hundreds of temperature sensors buried in the base of the road, sending a flow of data – a sort of early warning system should something go amiss. But, past all this, the most striking aspect of the construction was the timing. So as to take no chances with damaging the perma-frost, the build took place only during the winter months. For four years, construction was undertaken only from November to March, in constant temps of -24 to -60 C, often in complete darkness for weeks at a time.

Crews worked 24 hours a day from both ends of the road till completion. Three-hundred million dollars later, the official ribbon cutting took place on Nov 15th of 2017, with this past summer seeing just the first trickle of tourist traffic arriving in Tuk – including me in the new Silverado in mid-September (when it was already -10C).

This is an aspirational road – one that many Canadians and our cousins from further south will want to drive. It is destined to become one of those “I did it because it was there” stretches of road. If you do go – it’s well worth it.